Individual articles from the Fall 2020 issue of Intersections will be posted on this blog twice per week. The full issue can be found on MCC’s website. This article consist of five reflections which will be posted separately.

As MCC approached its centennial year, we asked Anabaptist leaders from Canada, the U.S and across the world what their visions are for MCC’s second century of service. As we look ahead to MCC’s second century of service, may the visions offered below spur discernment guided by God’s Spirit about what relief, development and peace in the name of Christ will look like over the coming years and decades.—The editors.

Serving together as Anabaptists

Just like God realized his purpose in creation, so did he call and inspire a few with the vision to serve “in the Name of Christ” through MCC a hundred years ago where there was suffering—physical, emotional and spiritual. These pioneers were gifted and equipped with wisdom by his Spirit to function as the service arm of the church. It was with a new heart and a new spirit that the work of MCC began a century ago. Of the one hundred years that MCC has served in various parts of the world, 75 have been in India. I was immensely blessed to have worked with MCC for half of those 75 years.

“More and more people in the pew in India express a better understanding of what it means to serve as Anabaptists, recognizing that Anabaptist distinctives call us to work in unity to challenge unjust systems in which we live as a minority community.”

We have heard, seen and experienced how MCC has delivered relief, development and peace programs—and continues to do so directly and in partnership with churches through its faithful, committed and dedicated personnel. MCC India has sought to engage India’s churches, including Anabaptist churches, as the church reaches out to deliver services to all, irrespective of caste, creed and colour. Looking back at MCC India’s long history, one can only marvel at the huge impact made on countless lives without creating dependency. MCC India has made this impact because it has strived to live up to MCC’s core values: working with all people in distress; partnering with local churches and organizations to be the ‘light’; and facilitating transparency, mutual respect and sustainability through its initiatives.

MCC India has invited churches to share, learn and understand MCC’s vision and priorities through meetings and workshops. One such partner, MCSFI, is the national body of Anabaptist churches in India and Nepal. MCC has taken upon itself to strengthen MCSFI so that the churches’ dependency would be more on local initiatives and less on MCC, even though this has been met with resistance. However, through sustained efforts, this has resulted in better and closer relationships between MCC and the churches. Through it all, MCSFI worked to strengthen its ties to its member churches, in addition to implementing social initiatives.

“Looking back at MCC India’s long history, one can only marvel at the huge impact made on countless lives without creating dependency.”

My role as MWC South Asia regional representative for India and Nepal has helped me better understand the challenges our churches face, as well as know how some churches are growing despite insufficient financial resources, inadequate pastoral training and challenges in identifying committed younger leaders.

During the past few years, the relationship between churches and MCC has improved considerably. More and more people in the pew in India express a better understanding of what it means to serve as Anabaptists, recognizing that Anabaptist distinctives call us to work in unity to challenge unjust systems in which we live as a minority community. MCC’s personnel need to continue working closely with churches, sharing the MCC story and reflecting with them about what it means to be a peace church in the Indian context. Furthermore, churches who in the past received much from the outside are now less dependent on those resources and are learning the hard way to be more dependent on God and local resources. This trend must continue so that MCC and its church partners work in ways that benefit both, resulting in dignity, maturity, accountability, transparency, integrity and above all love of God that permeates to and through all people, irrespective of caste, creed or religion.

Cynthia Peacock is South Asia regional representative for Mennonite World Conference.

Serving others around us

Among Beachy Amish Mennonites, the vision for service is focused on being both personal and practical. Our service is personal because we believe that all our service flows out of our love for God and a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. Because we love God, we reach out to serve others as an expression of our calling to represent him to those around us.

“Our service is personal because we believe that all our service flows out of our love for God and a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.”

Our service is personal because we believe we are called to serve personally. While we also support others who serve on our behalf in organizations like MCC, we believe strongly that each Christian is called to serve personally and should be directly involved in meeting needs around them. We believe that personal service helps each servant grow in humility and the Fruit of the Spirit which then enhances their service even further.

Our service is personal because we believe that the best service is given face-to-face in a personal relationship with the person in need. Serving others around us is given priority over supporting programs far away in which others make the actual contact. We want to develop friendships with those whom we serve. We believe that this broadens the perspective of the servant and the served as well as provides greater opportunity to live out the Gospel in a way that impacts others most significantly.

Our service is practical because we believe that it is not so much something we do as something we are. As a consequence, we are not focused on looking for the opportunity to make the biggest impact but on the opportunities, large or small, that God brings our way. We emphasize that the “cup of cold water” given in love as Christ’s representative is just as significant in the sight of God as some big gesture that makes the news.

Our service is practical in our emphasis on meeting the needs that God presents to us at the moment, from changing a tire beside the road to bringing comfort along with the casserole to a grieving neighbor. Our service is practical in our emphasis on serving our community and the broader world one person at a time. We believe that loving, person-to-person service is the best way to represent Jesus to the world. Our service is practical in our acceptance that it is God who brings fruit from any endeavor, understanding that he doesn’t need us to do his work but he graciously gives us opportunity to assist God in what he is doing, much as a parent will allow his young child to “help” with the project at hand. This allows us to enter into service without needing to “get it all right” the first time, to bumble around a bit finding our way, to step out in faith even when we aren’t sure what we are doing or where we are going. We believe that a sincere love speaks Christ more clearly than a ‘perfect’ program or message can without it.

“We believe that loving, person-to-person service is the best way to represent Jesus to the world.”

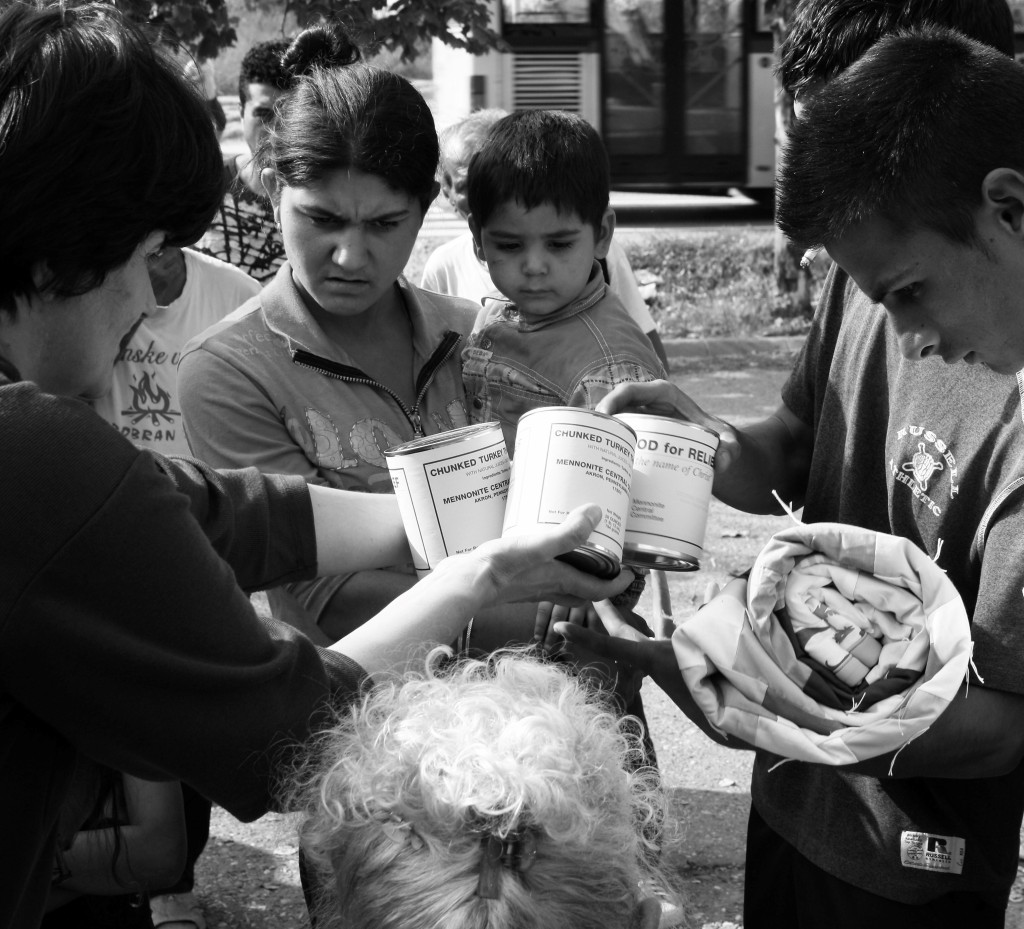

MCC’s opportunity to partner with Beachy Amish in the U.S. will continue to center around the practical opportunities to serve such as meat canning, comforter knotting and kit packing. Involvement in practical service projects such as MCC’s house repair project through the Sharing with Appalachian People (SWAP) program could be another point of contact. Beachy Amish will welcome exploring these types of practical opportunities to serve with MCC.

Tim Miller is bishop of McKenney Mennonite Church (Beachy Amish) and serves on the board of the Beachy Amish Peace and Service Committee and with the Conservative Anabaptist Service Program.

Linked by Christ’s Spirit in holistic mission

It is such a pleasure to add my well-wishes to MCC’s centennial celebrations! Countless individuals have been blessed by the ministry of MCC—those around the world who have benefitted from MCC’s relief and development work of MCC and those who have found a new measure of peace through MCC’s work of reconciliation and peacemaking. Of course, MCC has also blessed those countless individuals who have connected with MCC as volunteers.

“We are linked by the Spirit of Christ who clearly sends his Church on a holistic mission—a mission of word and presence, a mission of sharing the good news of Christ and helping to relieve the hardships of life.”

The Mennonite Brethren (MB) in Canada are intricately linked with MCC through our governance structures and through our people. There are countless MBs in Canada who meaningfully contribute to the work of MCC as staff and as volunteers, whether by packing relief buckets, sewing quilts, promoting MCC events or helping in the many Thrift shops. In addition, our congregations and individuals gladly give millions of dollars each year to MCC’s ministries, without special giving appeals, but rather simply out of conviction about the crucial nature of the work.

Even more importantly, we are linked by the Spirit of Christ who clearly sends his church on a holistic mission—a mission of word and presence, a mission of sharing the good news of Christ and helping to relieve the hardships of life. The person and work of Jesus are our primary motivators behind our enthusiastic support of relief, peacemaking and development.

The leadership of the Canadian Mennonite Brethren Conference of Churches is recognizing anew that the local church was designed by God to be at the forefront of God’s Kingdom work. We are focused at coming alongside the local church to support and empower the church to accomplish its calling and mission in its particular setting.

MCC has unequaled expertise in global relief, the work of peacemaking and reconciliation and creative development of micro- and macro-economies. Each of these areas of expertise are incredible resources which have the potential to empower each local church in its specific call. I would love to see MCC increasingly visible and active in the local church, sharing the lessons learned over one hundred years of ministry experience.

“The local church was designed by God to be at the forefront of God’s Kingdom work.”

Training and equipping in peacemaking and reconciliation principles, scalable to the lives of individuals and communities in our western context, would place invaluable tools into the hands of followers of Jesus. The ever-increasing presence of refugees in our world calls for cross-cultural awareness in our contexts here in Canada as we bring the reconciling message of Christ to our new neighbours. The Lord has also opened doors to ministry among our First Nations peoples where the lessons learned by MCC on a global scale certainly apply.

Gospel mission is a key strategic priority for the Canadian MB Churches. We consider MCC a key partner in helping us take fresh and courageous steps in this area. MCC has demonstrated creative thinking and problem solving over the past one hundred years. The church in Canada needs MCC to continue to be on the leading edge of relief, peacemaking and development strategies to inspire and to equip the local church to creatively and boldly witness to the manifold deliverance our Lord Jesus brings. May the mercy of the Father, the grace of Christ and the power of the Spirit carry the mission of MCC into the next one hundred years.

Ingrid Reichard serves the Canadian Conference of the Mennonite Brethren Churches as the National Faith and Life Director.

Discerning the times

The beginning of a new century for MCC and its church partners presents a good opportunity to discern the times and assess global and regional realities, paying attention to the accelerated changes shaping these contexts. New eyes and new ears are required to see, hear and respond to the movements of the Spirit and to build peace in the name of Christ.

“We must recognize the interrelationship between human beings and all the other beings that make up this world.”

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus tells his listeners to pay attention to the signs of the times rather than simply engage in weather forecasting: “You know how to interpret the appearance of the sky,” he tells the Pharisees and Sadducees who sought to test him, “but you cannot interpret the signs of the times” (Matthew 16:1-3, NRSV). Jesus recalled for his listeners that secular and divine events both require the same attention. God’s presence and action animate events. Jesus underscores to his listeners that they must view the events of everyday life with new eyes, discern God’s Spirit moving through those events and then respond to where the Spirit is heading.

For MCC and the church to discern the times at the start of MCC’s second century will involve:

“Discerning the times means analyzing and agreeing on what is happening in our respective contexts and then aligning our understandings of mission accordingly, pointing towards the Kingdom of God.”

- Acquiring ecological awareness and valuing and respecting creation and the dignity of life. We must recognize the interrelationship between human beings and all the other beings that make up this world.

- Being committed to and respecting human rights, as well as civil and political rights based on the principles of freedom and equality. We must in turn link the principle of freedom to the principles of solidarity and responsibility.

- Recognizing that the church and faith-based organizations are called to open up to gender, racial, religious and cultural differences. Each human being is a creature of God, bearing dignity and created in God’s image.

- Raising their voices against war and sexual- and gender-based violence, including sexual abuse and harassment within faith communities.

- Commitment to ecumenical and interreligious dialogue.

- Addressing migrations and forced displacement as global, massive and complex phenomena. The number of people on the move is higher than ever before, including refugees displaced by violence and war and people forced to search for livelihoods and better living conditions.

Discerning the times means analyzing and agreeing on what is happening in our respective contexts and then aligning our understandings of mission accordingly, pointing towards the Kingdom of God. Discernment can lead to revisions and realignments that might be threatening to dogmatic and fundamentalist approaches. Yet when we listen to God’s Spirit, the church and MCC can be opened up to respond in the new and creative ways demanded by our present reality.

Alix Lozano is a Colombian Anabaptist theologian, teacher and pastor.

Land, broken relationships and the task of reconciliation

They don’t need something new.

They need to go back.

They need to remember the original call.

With a warm smile my friend lifts up a passionate summons to action as we share coffee at Canadian Mennonite University’s Folio Café. Adrian Jacobs is Haudenosaunee, a member of the Six Nations of the Grand River. Currently the Keeper of the Circle at the Sandy-Saulteaux Spiritual Centre, he worked with MCC Ontario from 2007 to 2010 in the Haldimand Tract, nurturing conversations in congregations around the Caledonia land dispute. At the time, many Christian settlers asked: “What can we do to repair the relationship?” According to Adrian, the Six Nations response was clear and consistent—

Remember the Two-Row Wampum, and live into it.

Remember our ancient and still living covenant—its call for peace, friendship and respect.

Remember the abiding principles of self-determination.

Remember the sharing of the river of life and this land.

Remember, and live into it.

“In their desire to do reconciliation, church communities are continually looking to do something new, regularly forgetting the past or impatiently moving on from it. But for Indigenous peoples, we believe we can only go forward as we look back.”

—Adrian Jacobs

“Church communities are caught up in the dominant logic of western progress,” says Adrian, as his hands move, one in front of the other. “In their desire to do reconciliation, they’re continually looking to do something new, regularly forgetting the past or impatiently moving on from it. But for Indigenous peoples, we believe we can only go forward as we look back. And that’s why, today, we’re still waiting for churches. Waiting for them to act on what we have given—to embrace the Two Row and the spiritual covenant.”

As I listen to Adrian, I can’t help but remember the radical re-orientations of the prophets Jeremiah and Micah. “Consider the old paths.” “Has God not shown you?” You know all this! “What is good?” You’ve been told. “Do justice.” Live the covenant. “Seek the good ways,” the foundational calls. And walk in them.

In Canada and the United States, we all know why the Indigenous-Settler relationship is broken. I’m talking about the big reason. Cultural misunderstanding, lack of education, plain old ignorance and racism are all part of the brokenness of the Indigenous-Settler relation. But alongside and underlying these factors is the issue of land. Land taken. Land stolen. That has always been the fundamental issue. And that is still the issue.

“Let us remember our promises, not with nostalgia, not with complacency, but with fierce determination, risk-taking love and renewed commitment.”

What then does that mean for those of us who long to live MCC’s mission of sharing “God’s love and compassion for all in the name of Christ”—and to share it here? I do not think it means that our predominantly settler organizations and communities of faith can’t do good reconciliation work by taking up matters that don’t address the ultimate source of the fracture head-on. We can do indirect work, and we do—all the time. But it does mean this. Some of us, and many more of us, must focus our concerted efforts specifically on land. As two anti-colonial theorists, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, put it, if the central operation of settler colonialism—this ever-present power that usurps Indigenous jurisdiction throughout Turtle Island—is the theft and exploitation of Indigenous lands, then it’s evident: the repatriation of Indigenous land and life must be at the heart of any true decolonizing praxis. That is true sharing of God’s love and compassion.

This is not news to anyone in MCC. Moved by Indigenous nations and partners, stirred by the witness of Native Concerns and the Aboriginal/Indigenous Neighbours programs, MCC has lifted up, time and again, a series of prophetic calls that address this great and most central wound.

Remember 1987. A New Covenant. “We believe that basic dimensions of Aboriginal rights need to be recognized.” “The right to self-determination.” “The right to an adequate land-base.”

Remember 1992. A Statement to the Aboriginal Peoples of the Americas. “We promise to work for the just and honourable fulfilment of outstanding obligations related to land, the resolution of conflicts over industrial development and other areas of dissonance.”

Remember 2000. A Statement on Aboriginal Land Rights (released by the Aboriginal Rights Coalition, of which MCC was a part). “The focus of our joint message . . . is to invite the people of our churches . . . to support a fundamental goal of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples: the provision of an adequate land base for First Nations, with sufficient resources for sustaining viable economies.”

Remember 2017. A Response to the TRC Calls to Action. “MCC repudiates concepts used to justify European superiority over Indigenous peoples [and land!], such as the Doctrine of Discovery.”

For decades, MCC has known what needs to be repaired for true reconciliation to happen. And with tremendous courage, it made a series of daring declarations pledging itself and the broader Mennonite constituency to that primary work of land justice.

When we look back on those same decades, we behold many beautiful efforts by MCC staff and program to flesh out these land-oriented commitments. We find MCC actively supporting the land claims struggles of nations like the Innu, Gitxsan and Lubicon. We see MCC present at the Oka, Ipperwash and Standing Rock-Dakota Access Pipeline crises. We discover MCC walking with the Young Chippewayan Cree and other landless bands. We note MCC’s hard work at the United Nations in support of the basic Indigenous rights to land and life articulated in the Declaration. And we witness MCC issuing Jubilee grants each year to support Indigenous-led reparative efforts.

There is some remarkable history here. But I am not sure who all knows this tradition and the deep promises that both accompany it and call us to even “greater works than these” (John 14:12, NRSV). In my ministry, I am lucky to criss-cross these lands some call Canada and visit Mennonite congregations all over. I regularly lift up our MCC land engagements and land promises. Most, not surprisingly, are unaware. Yet most are incredibly heartened to learn about them. When they discover this rich and even radical history, it creates space, precedent and resolve for them to do reconciliation work that approaches the most fundamental issue.

As MCC celebrates its centennial and ponders how it might partner with the church in the years ahead to do the work of reconciliation, my encouragement is for us to walk into that future by looking deeply and courageously back. Let us remember our promises, not with nostalgia, not with complacency, but with fierce determination, risk-taking love and renewed commitment. The truth is, we do not, in one real sense, need to create anything new. For sure, there are different strategies and tactics that we can and should employ to be more effective, there are better or more relevant ways to mobilize Anabaptist churches into genuine faithfulness and solidarity work. But the first and most important step is to remember. Go back to the original call and covenant. Remember the Two Row. Remember our promises. Remember those who actually took those vows seriously and paid a cost. And together, let us follow that good way.

Steve Heinrichs is director of Indigenous-Settler relations for Mennonite Church Canada and lives in Treaty 1, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

The body of Christ, the body of the world

“Holding together the social and ecological dimensions of concurrent catastrophes is crucial.”

As I reflect on MCC’s motto, “In the Name of Christ,” I want to commend MCC workers who have grappled over time with the motto and its meaning. I was on the steering committee of the New Wine New Wineskins revisioning and restructuring process in my role as the North American representative of Mennonite World Conference’s Youth and Young Adult Executive Committee. During one huge meeting in Winnipeg, Canada, I saw MCC administrators, frontline workers and some community partners literally pace around in heated debate about whether to keep using this slogan or to drop it—if it was the essence we must communicate or a stumbling block to deepening partnership across lines of religious difference. Reflecting specifically on the question of whether MCC meat can labels should bear the slogan, “In the Name of Christ,” people talked about the where, when, why and how of everything related to these five words. “The more important issue is that it was written around cans of meat, and the folks we met wanted rice and beans!” one person exclaimed. “We saw people care less about the label and get right into the turkey!” another retorted. “We never translated it, and it was unclear if the receivers could read what it said, though they asked if [the meat] was halal,” a third said. “In my day I received quite a few quizzical looks from bureaucrats with regards to these words,” a quieter participant finally admitted. “Being obviously religious got us into places we could never go otherwise,” someone added.

“I challenge the church to send more people to serve with MCC, and for the church to listen even more closely to what these MCC workers have to say upon return.”

Words matter, not in the least because words create worlds. Christians profess belief in a God who created this precious world with words and invited humans to interact with their worlds through words and cooperation. In contrast, the prevailing creation stories at the time the Hebrew creation narrative was recorded often featured divine violence, hierarchy and forced labor as central themes in the creation of the world and the human interaction with the divine and each other. And as John 1 alludes to, our peacemaking witness—the refusal to perpetuate violence because of our commitment to following the Word made flesh —thus can be found at the very beginning of our scriptural tradition.

The debate was so heavy in Winnipeg because of deep grief for how the Christian story has been so distorted over time by those who have used violence to dominate, dispossess, control and displace. Many of the crises that MCC has responded to since its beginning have their roots in horrors done also “in the name of Christ.” Was our little part, as MCC, making a corrective to this legacy or in fact furthering it by promoting charity over justice or by needing to broadcast our perspective? My guess is there has never been a time when these topics weren’t a hot debate among MCC workers. Although it mostly occurred far away from Anabaptist meetinghouses, the debate like that which I witnessed was real church work. I hope the church (and all who support MCC) can see how service makes us do theological work, although the forms such theological work takes may be different from context to context.

If I started this article by writing about the beginning, the times now push me to speak of the end. We are in apocalyptic times, revelatory times—some say the time of Revelation. Yet apokalypsis in Greek simply means to unveil, to expose. These are indeed times where violence is becoming more obvious than before to more people than before. One initial thought is that this gives MCC the opportunity to connect with more non-Anabaptist Christians that want to make disaster response and relief, sustainable development and justice and peacemaking central to their discipleship practices. People across many denominations are catching of vision of what it means to be a peace church. What better organization than MCC to assist these Christians in living out a peace church vision that MCC has sought to operationalize for a century? I was happy to see MCC had a recruiting booth at a post-evangelical gathering last year, along with advertisement in an ecumenical magazine. It would be great for all of us to welcome the faithful from all traditions and backgrounds to serve together—it enhances our learning.

The letter at the end of our Bible penned by a political prisoner to the dispersed communities practicing redistributive justice “in the name of Christ” calls its readers to remain true to life even as the ground trembles, the oceans roar and fires engulf large areas of land. What to do now when those metaphors are featured in real life on daily weather reports as global temperatures reach record highs? As dead babies wash to shore as families flee violence? I breathed a sigh of relief when I read that MCC will focus on addressing climate change, especially naming the ways in which it accelerates violence and increases deprivation. Holding together the social and ecological dimensions of concurrent catastrophes is crucial. This holding—yet another tension to hold!—is deeply within the purview of an organization working in the name of Christ. Just as different parts of the body (1 Corinthians 12) cannot say to others that they have no need of them, we cannot say to the trees, “I have no need of you.” For trees breathe in what we breathe out and we inhale what trees exhale. The body of Christ is the body of the world. The world is being crucified at this time, by the crowds of us who cannot seem to see the possibility of non-coercive options and by imperial systems that crush all who build grassroots power. The world rises again—and the people rise again. To serve in the name of Christ is to serve in the name of this Earth, for they are groaning together for redemption and the revelation of the children of God (Romans 8).

Even if your theology does not match the ecotheological vision I have sketched above, I think it is wonderful that both of us have a place in MCC to work together to alleviate the suffering of humans and the Earth. I would like to see MCC become even more inclusive and make more room for everyone. I had transformative experiences working on assignments and volunteering with MCC and I want all to have access to the opportunity to be at the creative edges, holding the tension of joy and sorrow, working it out between Genesis and Revelation in the grey areas where the black and white text blurs together with our tears and sweat. As MCC enters its second century, I am confident MCC will be there at those edges, but I wonder: will the church be there? I challenge the church to send more people to serve with MCC and for the church to listen even more closely to what these MCC workers have to say upon return.

Sarah Nahar (née Thompson) began as an MCCer with MCC’s Summer Service program in 2004. She is currently a doctoral student in religion and environmental studies in Syracuse, New York (Haudenosaunee traditional land).

Centered, rooted, connected

I am grateful for the invitation to offer some reflections on my vision of how MCC can partner with the church in MCC’s second century. Vision is a word that is often used today. In our ordinary everyday life, vision is most often understood to be our ability to see things clearly—to see things as they really are, not blurry or distorted. But when vision is used with reference to the future it is understood to mean our hopes, our dreams, our aspirations, our desires, our wishful thinking. The following names some of my hopes and dreams for the future of MCC.

“MCC is a community of persons who are called to be Jesus-centered, Jesus-followers and Jesus-imitators.”

I wish for MCC to remain centered. As Anabaptist Christians, we believe Jesus is the center of it all. Before it is anything, MCC is a community of persons who are called to be Jesus-centered, Jesus-followers and Jesus-imitators. I hope that the mission and ministry of MCC will remain “in the name of Christ.” In Jesus, by Jesus, in obedience to Jesus and for Jesus must remain the center of MCC’s existence and purpose.

I wish for MCC to remain rooted and committed. I hope that MCC remains clearly and unapologetically rooted in the legacy of the radical reformers—the rich and inspiring legacy of men and women who were willing to endure hardship in order to remain committed to knowing, loving and following Jesus. These hardships ranged from name-calling and labeling—radicals, Anabaptists—to torture and martyrdom. MCC must remain rooted in and committed to the Anabaptist values, perspectives and priorities that led to its birth and have guided its ministry over the last one hundred years. Deep roots in its Anabaptist heritage will help MCC remain committed to being radical, being different and being counter-cultural.

I wish for MCC to remain connected and connecting. I hope that MCC remains a ministry of Anabaptist churches. While we acknowledge the family of Christ is one, we also acknowledge that the family has multiple families. The Church is one; yet the Church has churches. MCC has been one way that churches can come together in ministry. In a world that seems to be increasingly fractious, MCC must remain committed to bringing together different branches of the family to serve with love and compassion in the name of Christ, who is Lord of all. To that end, it might be time for MCC to transition to a new name so that it does not appear to be only connected to one particular Anabaptist family.

“While responding to basic human needs and working for peace and justice are critically important, MCC must remain focused on the primary relational need of all humans—a right relationship with God.”

I wish for MCC to remain focused. Every part of the body has a role to play. The eyes are for seeing. The ears are for hearing. The hands are for touching and holding. Without diversity and specificity of role there would not be a functioning body. MCC seeks to share God’s love and compassion for all and is inspired by a vision of communities around the world in right relationship—right relationship with God, right relationships with one another and right relationship with creation. MCC must remain focused on this vision and committed to an understanding that it is a right relationship with God that becomes the foundation for the transformation of all other relationships. While responding to basic human needs and working for peace and justice are critically important, MCC must remain focused on the primary relational need of all humans—a right relationship with God. It is this understanding and emphasis that helps set apart MCC from other organizations who might also be working to serve others and foster peace and justice.

Alan Robinson is national director of the Brethren in Christ Church U.S. and former senior pastor of Carlisle (Pa.) BIC.