Individual articles from the Summer 2020 issue of Intersections will be posted on this blog each week. The full issue can be found on MCC’s website.

As the specter of war loomed in the late 1930s, Mennonites, the Church of the Brethren and Quakers (who identified themselves as the “Historic Peace Churches”) collaborated to advocate to U.S. government officials that provisions be made for conscientious objection to war. MCC officials represented diverse Mennonite, Brethren in Christ and Amish groups in these discussions with government and military officials. Together, the Mennonites, Brethren and Quakers were successful in securing an agreement to establish the Civilian Public Service (CPS) program, which would operate camps where young men would be stationed to carry out work of “national importance” in lieu of military service. These alternative service CPS camps would then fall under the authority of different civilian government agencies, while being operated by MCC and other church bodies.

We exited CPS persuaded that a life of voluntary Christ-followership demands constant service to other people.

—Marvin hein

MCC opened its first CPS camp on May 22, 1941 in Grottoes, Virginia. It would continue to operate CPS camps through March 1946. MCC’s first 25 camps all fell under the jurisdiction of the Soil Conservation Service, the Forest Service and the National Park Service. Over CPS’s nearly five years of operation, MCC collaborated with twelve U.S. government departments, including the Public Health Service, the Department of Agriculture and the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration. Of the 151 CPS camps or units that operated during World War II, MCC operated 60 of them on either a solo or joint basis. Records indicate that around 38% of the conscientious objectors who passed through the CPS camps were from different Mennonite churches (with 4,665 young Mennonite men out of a total CPS group of approximately 12,000). CPS men fought forest fires, worked at soil conservation, served as orderlies in mental hospitals and much more. MCC’s first CPS mental health unit opened in August 1942 in Staunton, Virginia. Mennonite experiences in CPS mental health units spurred post-war action for more humane mental health facilities, leading to the founding of Mennonite mental health centers such as Oaklawn in Goshen, Indiana, and Prairie View in Newton, Kansas.

CPS broadened ecumenical horizons for participants, bringing young men from diverse Anabaptist groups together—and with Christians from other traditions. MCC organized educational programs for Mennonite participants, publishing a series of booklets for those programs that covered Mennonite history and theologies of service and non-resistance. MCC sought to foster a spirit of CPS men being “willing second milers” rather than “conscripted Christians,” even as some CPS men chafed at rough living conditions, low pay and compulsory labor (and as some CPS men criticized the program for too-close affiliation with the government and the war effort). CPS service had different meanings for different participants: for some it was a religiously acceptable way of fulfilling a patriotic duty, while for others it represented a positive, proactive witness for the gospel of peace (and for some it was both).

In 1941, just before Pearl Harbor, I left public school teaching because I knew that once our country declared war, I could not supervise war bond sales.

—Mary wiser

Just as the war effort mobilized many women into the work force, so, too, did women become part of the CPS effort. Wives and girlfriends often moved to be based near and work at or close by the camps where their husbands and boyfriends were stationed. Some women served in the camps as nurses. Women’s sewing societies prepared “camp kits” to send to CPS that included bedding, towels, toiletries, stationery and stamps. Over the course of CPS’s operations, around 2,000 pacifist women lived in or near the 151 camps, with CPS even operating women’s units at eight state-run mental institutions.

The excerpted reflections below from CPS newsletters and reports show young Anabaptist men and women reflecting on the meaning of Christian service and peace witness, on broadened ecumenical horizons gained through service and on the meaning of cooperation with the state in a time of war.

CPS as Christian service

CPS work has meaning to the men who perform it as an expression of loyalty and love to their country, and of their desire to make a contribution to its welfare. It has still larger meaning as constructive service and ministry to human needs, and as a demonstration of a way of life in peace and love in contrast to the destructiveness of war and violence.

—from Mennonite Civilian Public Service Statement of Policy, approved by MCC Executive Committee, September 16, 1943.

We want to do more than take a stand against war… We believed in the spirit of nonresistance, but also in the power of love to overcome evil.

—Elmer ediger, 1945

CPS is a constructive witness to the way of love as taught by Christ. The fact that the government has not opened the way immediately to use CPS men in areas of more direct need such as relief and reconstruction has not been too disturbing even though many at home and in the camps as well as administrative officials sincerely desire such service and feel it should be made possible. Because the church desires relief service does not mean they will refuse to cooperate with the government in areas that they can use CPS men and which are constructive in nature. . . . [S]o long as CPS gives expression to this deep religious faith there will be support of CPS by the church. Should it become something else, or should the government disallow a religious expression, church support would no longer be forthcoming.” MCC hopes “that through the CPS experience men will deepen and grow in their faith in and love of God,” “that CPS will do works that are a witness to the faith,” “that the men in camp will be more than drafted men,” and that “the men will rise above the fact that they have been conscripted and look upon their status as an opportunity to hear testimony to a deep faith in God and God’s purpose for man.

“The Mennonite Hope in CPS,” Mennonite Central Committee CPS Newsletter 1/13 (March 19, 1943).

It has been stated that men in CPS are only going the first mile and that often grudgingly. That is far too true; but we can go the second mile. If we were not in CPS where could we better represent the principle of going the second mile? If we cannot go the second mile in CPS, then we are admitting that Christianity is not practical in every occasion.

—Abraham Graber (Amish CPS camper), Mennonite CPS Bulletin 3/24 (June 22, 1945).

To say that the men in CPS are going the second mile and overcoming evil with good is to look at the picture through rose-colored glasses.

—Anonymous CPS man, quoted in “Keeping the Vision Clear,” Mennonite CPS Bulletin 4/9 (November 8, 1945).

Leader, adjusts the parachute of

Harry Mishler at Civilian Public

Service (CPS) Unit No. 103 in

Huson, Missoula County, Montana.

Camp No. 103 was a Forest Service

base camp operated by MCC in

cooperation with the Brethren and

Friends service committees. It

opened in May 1943 and closed

in April 1946. Men in the unit were

highly trained, parachuting into

rugged country to put out forest

fires; in down times they performed

fire prevention work. (MCC photo)

Writing in the 1945 MCC Workbook, Albert Gaeddert observed “A weariness with the program.” “With too many campers there is a lack of active participation. Interests seem to center about personal convenience.” “We have discovered certain of our limitations. Selfishness is still very much a part of us. We are not free from greed and the things of this world.”

Most of us entered CPS largely because we had little choice. We exited CPS persuaded that a life of voluntary Christ-followership demands constant service to other people. For two years we had served our national government, the church and each other. Somehow the conviction that our lives were not our own was translated into an unshakable belief that we were destined as God’s people to serve the world.

—Marvin Hein, A Community is Born: The Story of the Birth, Growth, Death and Legacy of Civilian Public Service Camp #138-1, Lincoln, Nebraska 1944-1947 (self-published).

[T]hose to whom CPS has been a challenge and have had as their motive service for Christ and the Church will make excellent relief workers and am hoping that they will be able to go soon into all parts of the world to witness for what they believe.

—Ellen Harder (former CPS nurse, written while working with MCC at Taxal Edge, England) Mennonite CPS Bulletin 4/2 (July 22, 1945).

Broadened inter-Anabaptist horizons

In most instances [the discharged CPS worker] will be interested in cooperating more closely with other Mennonite groups. He will have formed acquaintances among them, which he will not forget and he may not always sympathize too much with old prejudices. He will know other Mennonites as they are.

—Unnamed CPS worker, MCC Workbook, 1945.

Bennie Deckert reflected that “when we were at home many of us lived largely to ourselves. We had very little contact with the outside world, with men of different denominations, occupations, different sects, communities and states. Our friends lived nearby, perhaps in our very local community. Now we know men from nearly every state, denomination, and from nearly all walks of life. To many of us Mennonites has come the realization that there is much more to the word Mennonite than is embodied in our own local group.”

—“Three Years in CPS,” Rising Tide (June 1945).

Women and CPS

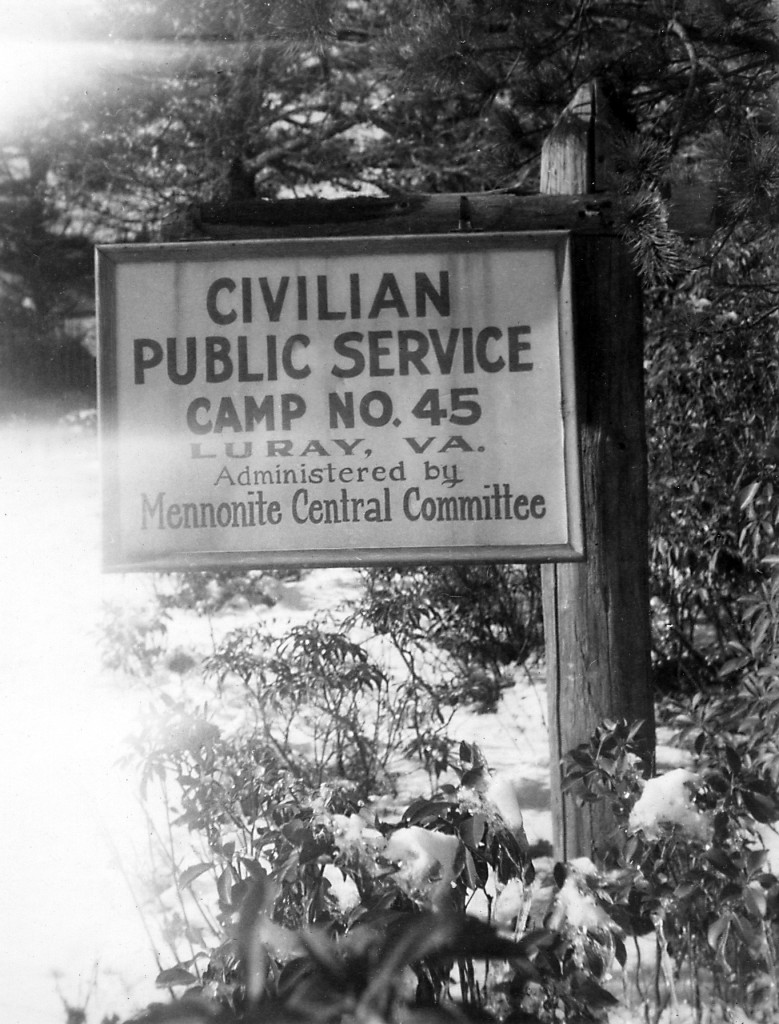

No. 45 Camp sign situated on the

Skyline Drive in Luray, Virginia. Camp

No. 45 was a National Park Service

base camp located in Shenandoah

National Park and operated by MCC.

It opened in August 1942 and closed

in July 1946. CPS men maintained

and improved park and recreational

facilities, including roads. They also

performed conservation and fire

prevention duties. (Photo courtesy of

Edgar M. Clemens)

Lois Schertz: “Even though the working conditions at the Mt. Pleasant State Hospital were deplorable, there were many good things that came from that experience for me as a woman. The unit became a family. We bonded together in a beautiful way, both men and women. For example, in our church services, men and women both participated. This was my first experience in being allowed to lead a worship service. (I went back home after the war and it took a good 30 years for that to happen).”

—Lois Schertz (served at CPS unit at Mt. Pleasant State Hospital, Iowa), “War, Alternative Service, and a Reality Jolt,” Women’s Concerns Report, no. 116 (Sept.-Oct. 1994), 5.

In 1941, just before Pearl Harbor, I left public school teaching because I knew that once our country declared war, I could not supervise war bond sales. Nor did I want to be part of the accelerating groundswell toward war that seemed to be required of public school teachers.

—Mary Wiser, “Searching for a Brotherly Life in a Warring World,” Women’s Concerns Report, no. 116 (Sept.-Oct. 1994), 8-9.

Expanded understandings of nonresistance and peace witness

We want to do more than take a stand against war. Many of us entered CPS with the vision that camp was the place where we could make a clear cut witness against war and for the positive aspect of our belief. We believed in the spirit of nonresistance, but also in the power of love to overcome evil.

—Elmer Ediger, Mennonite CPS Bulletin 4/4 (August 22, 1945).

Along with a stronger faith in the nonresistant position has come a greater sensitivity to the all-embracing implications of the Christian gospel. If nonresistance is held in regard to war only and not in attitude toward the mentally ill, the negro [sic], the under-privileged, employer, and fellow employees then nonresistance finds itself on the same level as a Sunday religion. In appreciating the totality of the way of love there comes a deep awareness of individual inadequacy, yet a drawing responsiveness to the call of Christ to permit him to penetrate every thought and act of our being.

—Unnamed CPS worker, MCC Workbook, 1945.

Mennonites, CPS and collaboration with the state

The irony of CPS was that Mennonites sought to remain free of governmental control, but by force of circumstances and tradition found themselves in one of the most intimate relationships ever established between church and state in American history, and with the military arm of the government at that.

—Al Keim, Gospel Herald, August 7, 1979.

Mennonites hold that it is the Christian’s duty loyally and faithfully to obey the state in all requirements which do not involve violation of the Christian conscience, that is, a violation of the teachings of the Word of God. They assuredly believe a Christian must obey God rather than man when the demands of the State conflict with this supreme loyalty to Christ but they also hold that the Christian should ‘Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s,’ and ‘Obey every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake.’ Although they acknowledge that it is within the province of the state to require service of its citizens, they reserve the right to refuse such service if it is contrary to conscience. This attitude toward state service does not constitute an endorsement of conscription or compulsion as such, but is rather an expression of the principle of obedience to the powers that be. In like manner, the Mennonite Central Committee takes a positive rather than a merely negative attitude toward the Selective Service Administration and other government agencies which are responsible by law and presidential directive for the administration of this state service.

—from Mennonite Civilian Public Service Statement of Policy, approved by MCC Executive Committee, September 16, 1943.

[I]t is quite possible to accept an evil compulsion in a Christ-like manner. But it is also a serious matter to judge anyone’s refusal to accept conscription as being un-Christian. For there are those conscientious objectors who cannot acquiesce to government pressure to perform civilian service in lieu of armed service because war and conscription for war are inseparable. We have a profound respect for the men who have worked with us within CPS before deciding that they must bear their witness in jail. They have been a continual challenge to us in our stand.

—Delmar Stahly, “Invitation to Conscription,” Box 96 (monthly publication of CPS unit in Mulberry, Florida) 2/1 (August 1945).

Alain Epp Weaver directs strategic planning for MCC. Frank Peachey and Lori Wise are MCC U.S. records manager and assistant, respectively.

The Civilian Public Service Story. Website. http://civilianpublicservice.org

Gingerich, Melvin. Service for Peace: A History of Mennonite Civilian Public Service. Akron, PA: MCC, 1949.

Goossen, Rachel Waltner. Women against the Good War. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997