[Individual articles from the Spring 2020 issue of Intersections will be posted on this blog each week. The full issue can be found on MCC’s website.]

The World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO) defines fair trade as a “trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers—especially in the South.” Fair trade organizations that produce and sell handicrafts, food items and more put these goals into practice through the application of the WFTO’s ten principles of fair trade, which include transparency, fair wages and good working conditions.

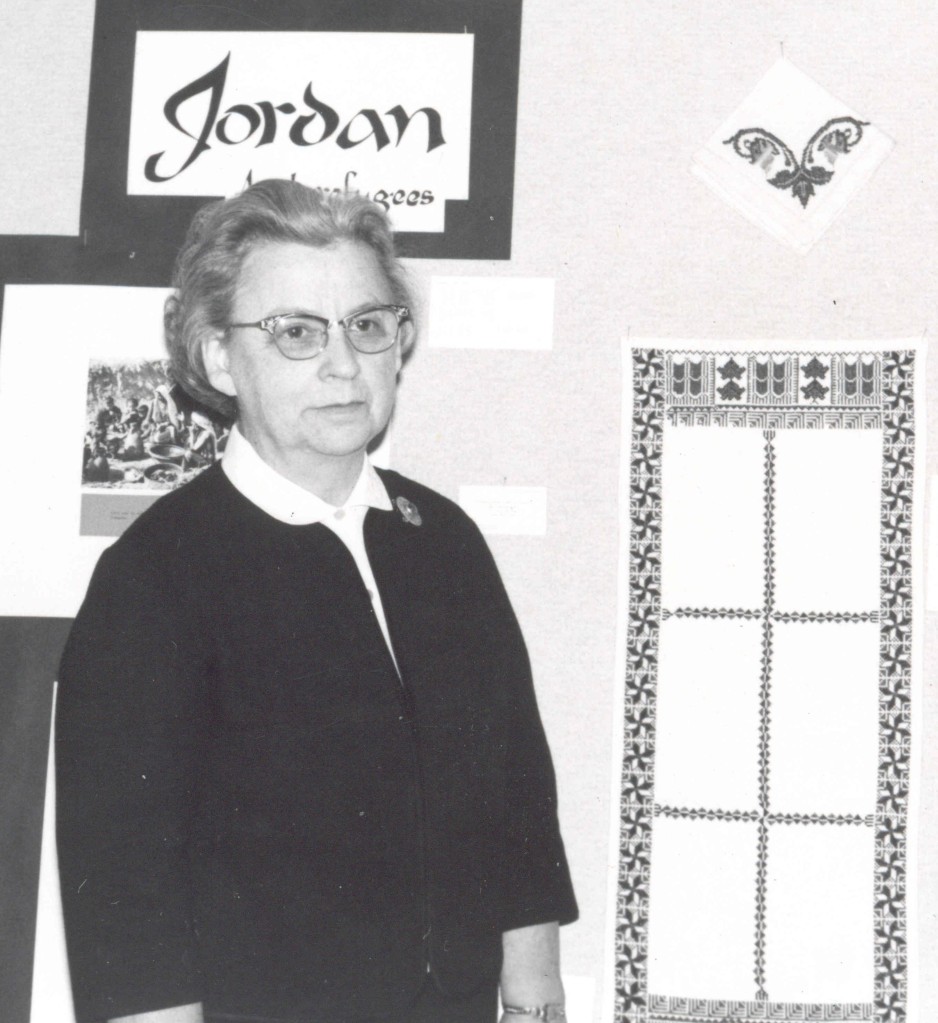

with artisan handicrafts from

Jordanian-controlled West Bank.

The grassroots “fair trade” effort

of Edna Ruth Byler provided

meaningful income for artisans

by selling their handicrafts.

(MCC photo)

Faith communities have played an important role in developing these principles and practices of fair trade, and Anabaptist communities and MCC are recognized as critical to the development of the fair trade industry in Canada and the Unites States. Anabaptist involvement in fair trade began with Edna Ruth Byler after she visited Puerto Rico in the late 1940s and saw the embroidery women were making but had no place to sell. She returned to the United States and began selling their work out of the trunk of her car and then in church basements and fellowship halls. Interest grew, and what started as a one-woman operation turned into SELFHELP Crafts of the World (hereafter SELFHELP Crafts), one of the first businesses to develop fair trade practices to benefit artisans. SELFHELP Crafts became an official MCC program in the mid-1960s, with headquarters in Akron, Pennsylvania, and a flagship store in nearby Ephrata. In 1965, this work expanded from the U.S. to marketing in Canada, with the Canadian Overseas Needlework and Crafts Project launching in Saskatchewan, and with the first SELFHELP Crafts of the World store in Canada opening in Altona, Manitoba, in 1972. SELFHELP Crafts rebranded in the 1990s as Ten Thousand Villages (referred to below simply as Villages).

MCC, through SELFHELP Crafts and now Villages, has been active in fair trade for nearly 75 years, with Villages’ mission to “create opportunities for artisans in developing countries to earn income by bringing their products and stories to our markets through long-term, fair trading relationships.” Through Villages, MCC has learned significant lessons about the impact of fair trade on artisan livelihoods. Most recently, MCC Canada commissioned an impact evaluation that examined artisan groups in India and Nepal to better understand the role Villages has played in advancing artisan livelihoods. While this study looked at a small portion of the work that Villages does, focusing on a limited geographic region, it identified lessons that are relevant to the breadth of Villages’ engagement with artisan groups and fair trade suppliers, lessons related to a) the impact on household income and socioeconomic status; b) the role of Villages in producers’ organizational growth; and c) the tensions between supporting artisans and compliance with WFTO standards.

Impact on household income and socioeconomic status: The evaluation found that handicraft sales represent an important source of income for artisans. For instance, handicraft work often comprises 50% to 75% of artisans’ total household incomes. No artisans, meanwhile, were found to be living below the poverty line. Many artisans highlighted the social supports they received through fair trade handicraft work, such as health care, literacy classes and improved communication skills. While the evaluation found that fair trade does have a positive impact, with artisans receiving regular income that allows them to send children to school, purchase food and clothing and receive social supports, quantifying the extent of this impact is extremely difficult due to the wide variety of producer groups with which Villages works. So, for example, Villages is only one of many purchasers to which most producer groups sell, making it difficult to single out the distinct impact of Villages’ purchases.

The historical role of Villages in producer organization growth and development: The impact of Villages on producer groups, however, is quite clear, as all groups noted that partnering with Villages strengthened their ability to produce and sell to other buyers when they first started. Villages is among the oldest buyers for groups, and the support and technical assistance provided over the years helped improve producer capacity and sales and build momentum and reputation. Support from Villages included flexible payment arrangements, shipping support, leeway with delays in fulfilling orders and payment advances (with Villages paying half the cost of orders upfront). The evaluation also noted that the long-term impact on producer groups by selling to a well-known and respected buyer like Villages and generating a long-term business relationship with regular orders and payments cannot be overstated.

Challenges and tensions between supporting artisans and compliance with WFTO: To be considered compliant with fair trade principles by the WFTO, producer organizations must submit detailed reporting that presents evidence for how they adhere to the WFTO’s ten principles of fair trade and its more than seventy compliance criteria. The evaluation noted that ensuring WFTO compliance and having a positive impact on artisans are different and often conflicting goals. Compliance requires significant investment in staff time, funding, data collection and management to meet reporting requirements and provide the level of detail needed. For small producer organizations that operate on small margins, it can be difficult to meet these requirements while also dedicating the time and resources needed for artisan capacity building and support.

Ten Thousand Villages and the broader fair trade industry have grown significantly from simple beginnings as a venture in the trunk of Edna Ruth Byler’s car. Shifting economic landscapes and rapidly changing business models force fair trade enterprises to compete in a challenging environment. The future of Ten Thousand Villages is in flux. In the face of flagging sales and consistent operational losses, MCC Canada made the difficult decision at the beginning of this year to close the ten MCC Canada-owned stores, along with its warehouse and its head office, by the middle of 2020. Eight Villages stores operated by local boards will continue to operate in Canada. Meanwhile, Ten Thousand Villages in the United States continues to reposition itself within a competitive market for brick-and-mortar sales, seeking to strengthen online sales and to develop distinctive “maker-to-market” sales spaces that connect consumers with artisans and their stories. Whatever the future holds for MCC and Ten Thousand Villages, MCC can take deep pride in having pioneered a global movement dedicated to ensuring that producers are treated and compensated fairly.

Allison Enns is MCC food security and livelihoods coordinator, based in Winnipeg.

Keahey, Jennifer, Mary Littrell, and Douglas Murray. “Business with a Mission: The Ongoing

Role of Ten Thousand Villages within the Fair Trade Movement.” In A Table of Sharing: Mennonite Central Committee and the Expanding Networks of Mennonite Identity. Ed. Alain EppWeaver, 265-283. Telford, PA: Cascadia Publishing House, 2011.

Littrell, Mary and Marsha Dickson. Artisans and Fair Trade: Crafting Development. Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press, 2010.

Raynolds, Laura T. and Elizabeth A. Bennett. Eds. Handbook of Research on Fair Trade. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015.